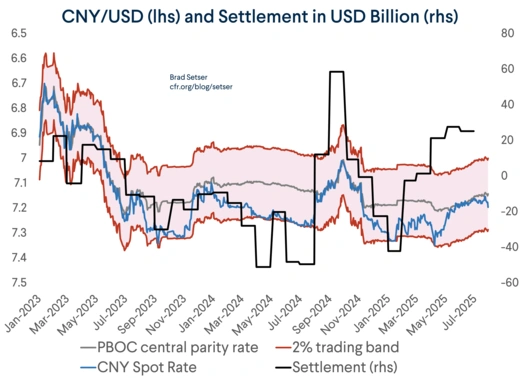

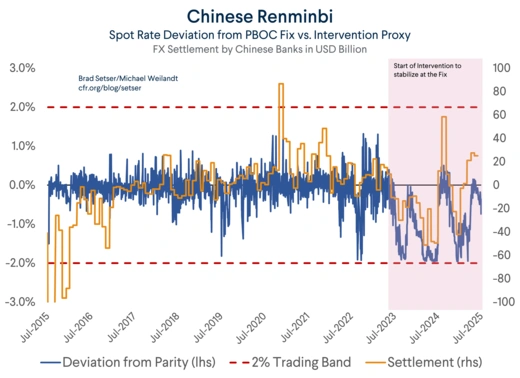

The daily Central Parity Rate (“fix”) is supposed to be the middle point in the daily trading band for China’s currency.* But a funny thing has happened over the last few years.

The onshore yuan almost never trades “strong” (numerically, a smaller number; the yuan is stronger if it takes six yuan to buy a dollar than if takes seven or more) relative to the fix.

More on:

In other words, it looks like—de facto—China has shrunk the band and shifted the role of the fix from the midpoint of the band to the upper end of the band.

That of course allows China a lot more control over its currency on a day-to-day basis. The fix defines the upper limit on the day’s appreciation, more or less. And when the yuan is under depreciation pressure, the fix minus two percent still sets the limit on how much the yuan can depreciate.

This matters for a host of reasons.

Once upon a time, China was aiming to reform its currency regime so that the fix sort of faded away, and the yuan could trade somewhat freely inside the band (which was expected to be progressively widened). That didn’t happen. Rather, the band was in effect shrunk and the daily fix gained importance rather than losing it.

This isn’t a total surprise. The PBOC’s institutional desire to move toward a market-determined exchange rate has always been balanced by the State’s Council’s desire for stability, and the Party’s continued interest in managing the financial account. See Logan Wright, who has been watching the PBOC closely for just about as long as anyone:

More on:

“China has never been fully committed to exchange rate stability, but has also never been interested in a completely market-determined currency either. As a result, markets have consistently speculated about the PBOC’s reaction function and how it will manage the currency, which has created significant swings in capital inflows and outflows over the past twenty years.”

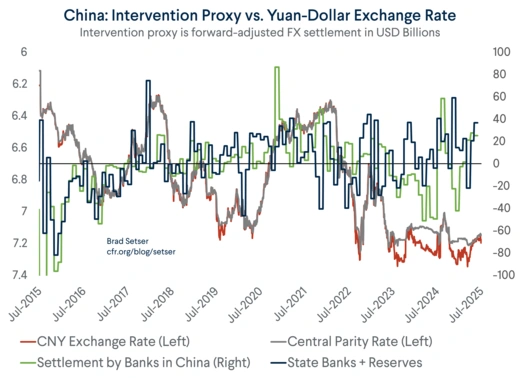

Having the fix as the upper band also—likely—simplifies communication with the state banks, who are now the main agents of China’s de facto intervention in the FX market (the yuan trades like a fixed or heavily-managed currency, yet there is no movement in the PBOC’s reported foreign currency balance sheet – which is strange).

In recent months, FX settlement by the PBOC and the state banks—long a critical indicator of China’s true intervention—has shown that the state banks are accumulating foreign exchange (settlement is positive) when spot is close to the fix. ** Look at the following chart closely, the state bank’s intervention rule seemed to shift in the middle of 2023.

That makes sense if the fix is effectively serving as the PBOC’s signal of its upper tolerance for a rise in the yuan.

In theory (or perhaps on paper) the band should imply that China’s central bank intervenes at the edge of the band to keep spot inside the band. In practice, half the band currently isn’t used, and the state banks seem to be intervening as needed to keep spot close to the fix and limit appreciation.

This highlights that there has been, frankly, less to China’s exchange rate reform than meets the eye. Particularly over the last few years the PBOC, apparently acting in conjunction with the state banks—is once again both managing the yuan primarily against the dollar and tightly controlling the yuan’s moves.

China’s de facto exchange rate regime is thus quite different from it stated regime.

This is fitting topic for the IMF if it really wants to get back to basics… and prove that it can be more than just a fiscal watchdog.

And in the broader context, it matters that China is now once again facing appreciation pressure.

In some sense, it makes it easier for those of us who want a more balanced global economy.

We don’t need to call for China to use its (ample) foreign exchange reserves to resist pressure for depreciation. Rather, we can simply call for China to allow the yuan to get stronger. That after all is the easiest way for China to wean itself off its current extreme reliance on net exports for growth.

* The yuan in theory can trade up to 2 percent stronger or 2 percent weaker than the fix.

** Technically, settlement includes the PBOC, but the PBOC’s on-balance sheet reserves have been falling by a steady USD 6-10 billion a month, so the rise is all on the side of the state banks. The net foreign asset position of the state banking system measure, which includes RMB denominated foreign assets, also has been increasing recently.