President Xi Jinping has set his sights on a “powerful” currency befitting China’s growing stature on the world stage, one that could challenge if not erode the U.S. dollar’s decades-long dominance in financial markets.

But the Chinese yuan, or renminbi, is unlikely to become a key player in foreign exchange reserves without sweeping structural reforms that Beijing has been hesitant to make, analysts say.

Despite lackluster consumer demand and a five-year housing slump, China still is by many measures in an enviable position. It is the world’s second-largest economy by nominal gross domestic product—and the largest in purchasing power parity terms—and it drove 30 percent of global economic growth last year, Chinese officials say.

China also boasts the largest banking system by assets, enabling it to fund large-scale infrastructure projects at home and abroad. It also has the world’s largest stockpile of foreign exchange reserves—a substantial buffer against financial shocks.

Yet for all China’s economic heft, the yuan remains a featherweight, accounting for around 2 percent of foreign reserves in central banks worldwide, compared with the greenback’s 56.3 percent, the euro’s 20.3 percent and the British pound’s 4.7 percent.

China’s financial institutions are weaker than those of advanced economies and the government has set strict limits on the amount of yuan that leaves the country. Beijing controls the currency’s value rather than allowing markets to determine the exchange rate, a practice that has kept trade deficits high and export prices low—much to Washington’s chagrin.

This managed system has helped shield China but has also limited its currency’s global appeal as a strong reserve asset, all in service of the long-ruling Communist Party‘s ultimate goal: domestic stability.

Xi’s Power Dream

Recent signals from Zhongnanhai, however, suggest renewed intent in expanding the yuan’s international role. China watchers say this interest is likely driven by an increasingly uncertain global landscape and doubts about U.S. stewardship of the dollar-based financial order under President Donald Trump.

China should work to build a “powerful yuan” with reserve currency status and broad use in international trade, investment and foreign exchange markets, Xi said in a 2024 speech that was given new life in a January 31 commentary published in Qiushi, the Communist Party’s main theoretical journal.

“From China’s perspective, the timing was ideal to repost an old 2024 speech by Xi, as global investors are speculating on a broader ‘weak dollar policy’ amid news on Fed’s credibility, joint USD-JPY intervention, Trump’s depreciation remarks, and the recent geopolitical upheaval, ”Kevin Lam, an economist at the Pantheon Macroeconomic analytics firm said in a recent LinkedIn post.

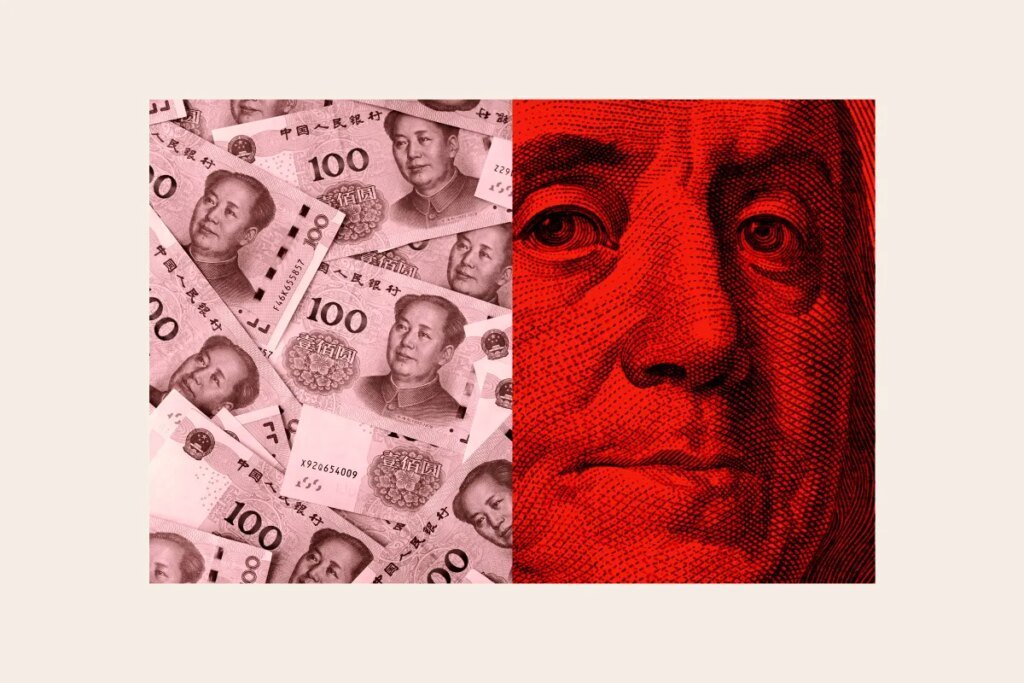

Getty Images/Newsweek Illustration

The yuan will “undoubtedly increase” its share of reserve holdings in emerging markets as they diversify to hedge against the fraught landscape, Eswar Prasad, an economics professor at Cornell University, told Newsweek.

This would be especially true in countries with strong trade links to China or those exposed to Western sanctions, such as Russia, which increasingly turned to yuan-denominated trade after being severed from the global financial system over its full-scale invasion of Ukraine.

Over the past decade, Beijing has loosened restrictions on foreign investors, including central banks, acquiring Chinese fixed income securities. This has “enticed many reserve managers in other countries to increase their exposure to yuan-denominated assets,” Prasad said.

But there were clear constraints, he said. “Since the renminbi remains a nonconvertible currency subject to capital controls and given foreign investors’ lack of trust in China’s institutional framework, there are limits to the renminbi’s rise as a reserve currency and especially as a safe haven currency.”

Limited by Design

Predictions that the yuan could be on the cusp of becoming a leading reserve currency were overstated, said George Magnus, an economist with Oxford University’s China Center.

“Apart from anything else, the Chinese government knows that even if they wanted it to be so—it’s far too risky to toy with this so soon and so fast,” Magnus told Newsweek. “China’s capital markets are far too immature and unconducive. It’s a tiny fraction of global reserve assets and likely to remain so.”

The obstacles are greater than a lack of full convertibility alone. A currency typically rises to reserve status when the rest of the world can accumulate large, liquid claims on the issuing country through open capital markets or persistent trade deficits—conditions China has historically avoided.

“To have a reserve currency, you need, among many other things, to allow foreigners to accumulate claims on you,” Magnus said. China’s policy framework limits both the scale and ease with which global investors can do so, he said.

Responding to arguments that advances in foreign exchange trading tech could help China sidestep these traditional requirements, Magnus said emerging tools primarily improve the speed and efficiency of transactions but don’t address the institutional foundations underpinning the yuan’s status.

“This is not about technology,” he said, arguing that credibility, openness and market depth—not trading mechanics—will ultimately determine whether a currency gains global trust.

China’s Foreign Ministry did not respond to a written request for comment before publication.