Getty Images

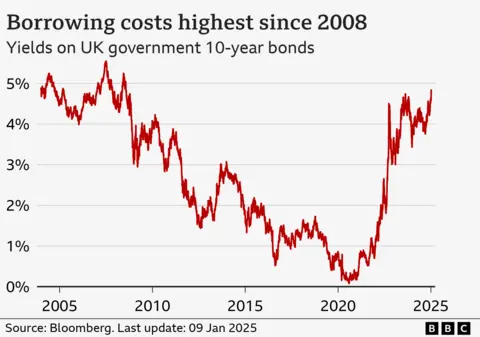

Getty ImagesThe pound has fallen to its lowest level in over a year, while UK borrowing costs hit their highest for 16 years.

Economists have warned that the rising costs could lead to further tax increases or spending cuts as the government tries to meet its self-imposed rule not to borrow to fund day-to-day spending.

In response to an urgent question in the Commons, Treasury minister Darren Jones said there was “no need for an emergency intervention” and markets “continue to function in an orderly way”.

But shadow chancellor Mel Stride said: “Higher debt and lower growth are understandably now causing real concerns among the public, among businesses and in the markets.”

Jones said: “It is normal for the price and yields of gilts to vary when there are wider movements in global financial markets, including in response to economic data,” adding that the government’s decision to only borrow for investment was “non-negotiable”.

But Stride said: “The government’s decision to let rip on borrowing means that their own tax rises will end up being swallowed up by the higher borrowing costs at no benefit to the British people.”

The pound fell by 0.9% to $1.226 against the dollar on Thursday, while borrowing costs jumped earlier in the day but calmed by mid-afternoon.

Sterling typically rises when borrowing costs increase but economists said wider concerns about the strength of the UK economy had driven it lower.

The government generally spends more than it raises in tax. To fill this gap it borrows money, but that has to be paid back – with interest.

One of the ways it can borrow money is by selling financial products called bonds.

Mohamed El-Erian, chief economic adviser at asset manager Allianz, told the BBC’s Today programme the rise in borrowing costs means the amount of interest the government pays on its debt goes up and “eats up more of the tax revenue, leaving less for other things”.

Mr El-Erian added that it can also slow down economic growth “which also undermines revenue”.

“So the chancellor, if this continues, will have to look at either increasing taxes or cutting spending even more – and that’s going to impact everyone,” he said.

The government has said it will not divulge anything on spending or taxes ahead of the official borrowing forecast from its independent forecaster due in March.

At the end of last year, revised figures showed the economy had zero growth between July and September.

It was the latest in a series of disappointing figures, including a rise in inflation in the year to November with prices rising at their fastest pace since March.

In December, the Bank of England said the economy was likely to have performed worse than expected in the last three months of 2024.

At the same time, it held interest rates at 4.75% citing “heightened uncertainty in the economy”.

But the Bank’s deputy governor Sarah Breeden said on Thursday that moves in the British government bond market had been “orderly”.

“We’re monitoring it,” Breeden said following a speech at the University of Edinburgh.

“So far the moves have been orderly. We do need to watch this space. So far, so good.”

Globally, there has been a rise in the cost of government borrowing in recent months sparked by investor concerns that US President-elect Donald Trump’s plans to impose new tariffs on imports from Canada, Mexico and China would push up inflation.

The cost of government borrowing in the US has seen a similar rise to that of the UK.

“It may be a global sell-off, but it creates a singular headache for the UK chancellor looking to spend more on public services without raising taxes again or breaking her self-imposed fiscal rules,” said Danni Hewson, head of financial analysis at AJ Bell.

Reeves v Truss

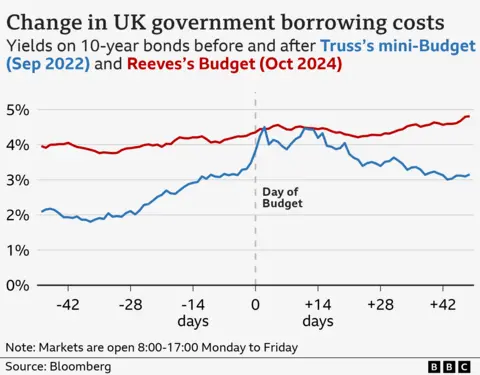

Some may be wondering about the impact of higher gilt yields on the mortgage market, particularly after what happened after Liz Truss’s mini-Budget in September 2022.

Although yields are higher now than they were then, they have been creeping up slowly over a period of months, whereas in 2022 they shot up over a couple of days.

That speedy rise led to lenders quickly pulling deals while they tried to work out what interest rate to charge.

But the picture is too complex to make a direct comparison between Truss and Reeves, said Simon French, chief economist at Panmure Gordon.

“The major driver of yields going higher under Truss was UK policy. It was a combination of the mini-Budget, which was her fault, and the energy crisis, which wasn’t her fault. But the mini-Budget was the biggest factor.

“This time, there is global anxiety about the level of debt pushing yields up everywhere, not least the US, which is not Reeves’ fault. But there’s also a dim view on the growth impact from her Budget, which is slowing rather than accelerating the economy. That is her fault.”