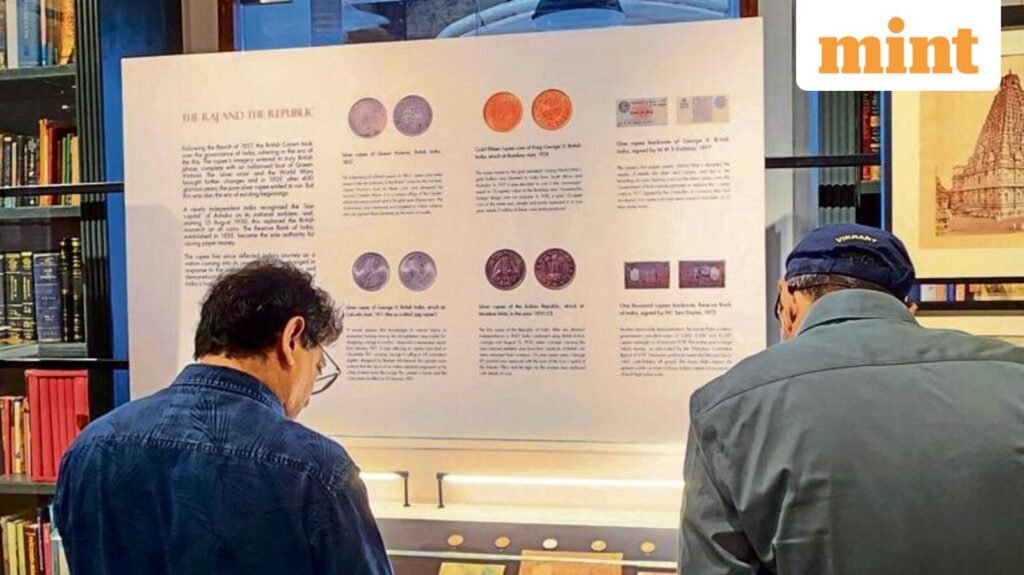

The humble rupee has a lot to complain about these days—it is a denomination often taken for granted, an exchange rarely accounted for and loose change that is never returned. But a walk through Mumbai-based Sarmaya Arts Foundation’s latest exhibition, Odyssey of the Rupee: From India to the World, relives the heyday of the rupee, a time when its aura and strength made it a universal symbol of power across centuries.

Most coins on display come from the private collection of Sarmaya’s founder, Paul Abraham, 65. It all started for him when as a young boy, his father handed him a bottle of coins from the kingdom of Travancore. Growing up in Delhi, Abraham spent his early days hanging out at coin fairs and exhibitions, soaking in India’s numismatic tradition that extends to over 2,500 years, while judiciously spending his modest pocket money. It has today grown into a diverse collection.

The exhibition, which runs until 31 January, was envisioned after a routine conversation between Abraham and his mate, Shailendra Bhandare, an equally passionate numismatist, curator at the Ashmolean Museum and faculty at Oxford University in England. It took Bhandare, Abraham and the team at Sarmaya about five months to weave a narrative around the rupee, even acquiring a few specific coins along the way that were missing from the collection.

“This is the 75th year of the first rupee of independent India that was minted on 15 August 1950. The history of the rupee goes back 500 years, so we thought of looking at multiple facets of this coin through the exhibition,” Abraham says.

Much before the rupee, ancient kingdoms of the Indian subcontinent made their own punch-marked coins—an exhibit from the Gandhara janpath from 600BC is among the older ones on display. The Islamic invasion in the 9th-10th century introduced coins devoid of symbolism as per the tenets of the religion and instead, displayed names of the rulers in calligraphy.

View Full Image

The first rupee is attributed to the Afghan king, Sher Shah Suri, who defeated Humayun to take control of northern India. When he observed different coinage being used across the region, he realised the need for a standard that would simplify trade. Silver weighing about 11.5-11.6m was recognised as the rupee or “rupya”, derived from “raupya”, which means silver in Sanskrit. “The Mughals were quick to adopt the rupee as formal currency of the empire, while Akbar was responsible for spreading its usage. It became a trusted standard and was widely accepted,” Abraham says.

“By the 17th century, it was a real choice for a lot of people because of its reliability. It became a bulwark of trade and that’s when the rupee really took off,” Bhandare adds.

Both Sher Shah Suri and Akbar’s rupees have been chosen as centre-stage exhibits for their importance in India’s coinage system. Such was the rupee’s superiority that kingdoms across the subcontinent adhered to the standard weight, while minting their own coins with symbols that highlighted their sovereignty—for instance, the Sikh coins display the leaf of the holy ber tree while coins from the riparian Awadh kingdoms have two fish depicted on them.

“So the first phase was adoption of the rupee and the second was its stabilisation, even as princely states showcased characters of their own during this period of Mughal dominance,” Abraham says. “The moment someone had aspirations to sit on the throne, they promptly minted their own coins. As a result, we keep finding new rulers in the Mughal pantheon. And their coins are more valued today since they are rare to come by.”

Once the British gained prominence, the hand-struck coins made way for well-crafted, machine-minted coins. But the colonial powers too realised the power of the rupee and persisted with it, even as they celebrated the crown with the first set of Queen Victoria coins in 1862.

Trade took the rupee all the way from East Africa to the Middle East and as far as present-day Papua New Guinea. Between 1880-1900, the Italians issued rupees in their colony of Somalia, as did the Portuguese in Mozambique and the British in East Africa. In fact, the Indian rupee was minted around the world—coins for German East Africa and Italian Somaliland in Berlin and Rome, respectively, and the Persian rupee in Tbilisi, Georgia.

“Until 1972, Oman still used the Indian rupee made by the Reserve Bank of India. From conquest to trade, the rupee had a fairly good run. There are fascinating stories associated with it. Mercenaries from little principalities issuing their own rupees, and regions such as Indonesia and East Africa that have a deep historical connection with the rupee. We’ll cover these varied aspects during special sessions over the next few weeks,” Abraham says.

The exhibition has little surprises across the foyer—a punch-marked coin from 500-450 BC found near Wai in Maharashtra, a Chinese silver coin in the format of the Victoria rupee minted in Szechuan, and a ₹10 bank note issued by the Reserve Bank to prevent gold smuggling.

According to Abraham, the paper rupee was started in the 18th century by a private bank called the Bank of Hindoostan, and the first one rupee note, which was issued as a promissory note, was in 1917.

The original maps, sketches and portraits from Sarmaya’s collection, the story of specific coins, a resourceful Google Map that marks out spots where the rupee has been minted over the years, and an absorbing Films Division documentary on the Reserve Bank makes this exhibition an afternoon well-spent, reliving the fascinating journey of the rupee.

Shail Desai is a Mumbai-based freelance writer.