India has a structural current account deficit (CAD) problem in its external balance of payments (BOP) transactions.

In the last 25 years and more, there have been only four fiscal years (April-March) of surpluses on the current account: 2001-02 ($3.4 billion), 2002-03 ($6.3 billion), 2003-04 ($14.1 billion) and 2020-21 ($23.9 billion).

In all other years, the current account — which captures the value of the country’s exports and imports of goods and services as well as receipts from and payments against international transfers and investments — has been in deficit.

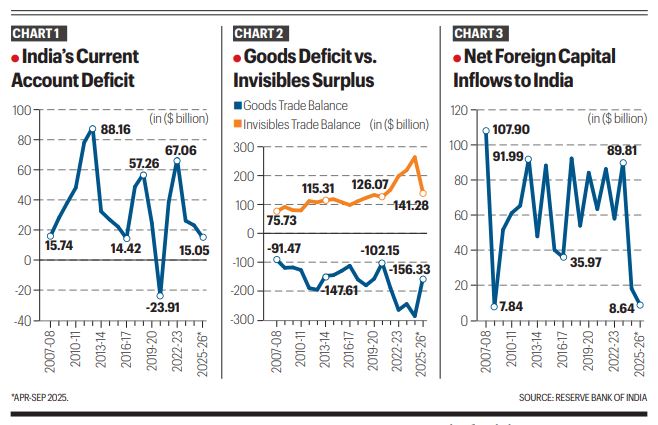

The CAD peaked at $78.2 billion in 2011-12 and $88.2 billion in 2012-13, but was contained within $50 billion for most years thereafter, except in 2018-19 and 2022-23 when it touched $57.3 billion and $67.1 billion respectively (Chart 1).

The invisible hand

The current account in the BOP has two subcomponents. The first is merchandise trade — exports and imports of physical goods.

India’s goods trade balance has always been negative, with the deficit more than doubling from $91.5 billion in 2007-08 to $195.7 billion in 2012-13. It narrowed to $112.4 billion in 2016-17 and $102.2 billion in 2020-21, only to shoot up and reach $286.9 billion in 2024-25.

Going by the trends during April-September 2025, the current fiscal could see the merchandise trade deficit cross the $300-billion mark.

Story continues below this ad

The widening goods trade deficit has, however, been significantly offset by the second so-called invisibles subcomponent. The “invisibles” trade has to do with the global flows of services, people, data and ideas, as opposed to the movement of tangible stuff (“visible”) across national borders through sea and by air.

In the case of invisible transactions, India has consistently enjoyed surpluses, thanks to receipts from private remittances or transfers and exports of software, business, financial and miscellaneous services. These receipts have considerably exceeded the outflows from payment of interest, dividends and royalty to foreign lenders/investors, and also other sources such as Indians studying abroad.

It can be seen from Chart 2 that the surplus on India’s invisibles trade has doubled from $75.7 billion in 2007-08 to $150.7 billion in 2021-22 and further increased to $263.9 billion in 2024-25. The current fiscal is likely to post a new record surplus, topping $280 billion.

The large invisibles surpluses almost counterbalancing the ballooning merchandise trade deficits is what has kept India’s CAD in check. While there are years (2011-12 and 2012-23 particularly) when the CAD has surged, it hasn’t really exploded to unsustainable or unmanageable levels.

Story continues below this ad

The rising invisibles trade surplus is reflective of India emerging as the “office of the world”.

Its information technology engineers, accountants, auditors, doctors and nurses have, to an extent, been what goods from China are, as the “factory of the world”

A capital crisis

From a strictly BOP perspective, the CAD has rarely posed problems for the Indian economy, while actually falling from $25.3 billion in April-September 2024 to $15.1 billion in April-September 2025.

The rupee’s recent slide — it has in the past one year depreciated against the US dollar (from 84.73 to 89.92) as well as the euro (89.20 to 104.82), British pound (107.76 to 120), Japanese yen (0.5658 to 0.5815) and Chinese yuan (11.66 to 12.72) — has been more courtesy of the capital, not current, account of the BOP.

Story continues below this ad

Chart 3 shows net foreign capital flows into India hitting an all-time-high of $107.9 billion in 2007-08. In subsequent years too, they were mostly higher than the CAD, thereby not only comfortably financing it, but adding to the country’s official foreign exchange reserves.

Capital flows include foreign investment (both direct and portfolio), commercial borrowings, external assistance and non-resident Indian deposits. The chart reveals net foreign capital inflows plunging to a 16-year-low of $18 billion in 2024-25, which was below the CAD of $23.1 billion for the fiscal.

A similar trend is discernible in 2025-26, with the first six months recording a mere $8.6 billion of net capital inflows, which is again lower relative to the CAD of $15.1 billion for the same period. The pressure on the rupee is, thus, clearly emanating from a drying up of capital flows rather than the CAD. The latter, if anything, has been on a declining path.

Among the components of capital flows, it is foreign investment into India that has taken the major hit. In net terms, foreign investment stood at just $4.5 billion in 2024-25 and $3.6 billion in April-September 2025. This was as compared with $54.2 billion in 2023-24, $22.8 billion in 2022-23, $21.8 billion in 2021-22 and $80.1 billion in 2020-21.

Story continues below this ad

Net foreign direct investment — which typically entails building of new factories, infrastructure and other physical assets, leading to creation of jobs — amounted to $43 billion in 2019-20, $44 billion in 2020-21, $38.6 billion in 2021-22 and $28 billion in 2022-23, as per the Reserve Bank of India’s BOP data.

It, then, slowed to $10.2 billion in 2023-24, before collapsing to $959 million in the following fiscal. There has been a slight recovery to $7.7 billion in April-September 2025.

The drop is even more apparent in foreign portfolio investments (FPI). During the five fiscal years from 2021-22, only one (2023-24) registered net FPI inflows of $25.3 billion into Indian equity markets. In all other years, foreign funds pulled out more than what they invested, translating into net outflows of $18.5 billion in 2021-22, $5.1 billion in 2022-23, $14.6 billion in 2024-25 and $4.3 billion in 2025-25 (till December 5), according to the National Securities Depository Ltd.

The drying up of foreign capital flows is, at one level, surprising given India’s high GDP growth rates.

Story continues below this ad

These averaged 8.2% per year from 2021-22 to 2024-25 and 8% for the first half of 2025-26. An economy growing at these rates would normally also attract capital flows from overseas investors keen to partake in that growth process.

Whatever be the explanations for foreign capital not coming into India like before, it is the most obvious reason for the rupee’s slump now.